“No bother Effendi” – The Orientalism of Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is one of the most successful adventure games of videogame history. LucasArts published the game in 1992 as a worthy successor of the (then three) Indiana Jones movies. Created by Hal Barwood, Hollywood screenwriter and also friend of George Lucas, it offered multiple ways of solving the game. Also, it used a sophisticated control as well as an ambient music system. It sold over one million copies, which was astronomical for the 1990ies. This article is about the Orientalism of Indiana Jones.

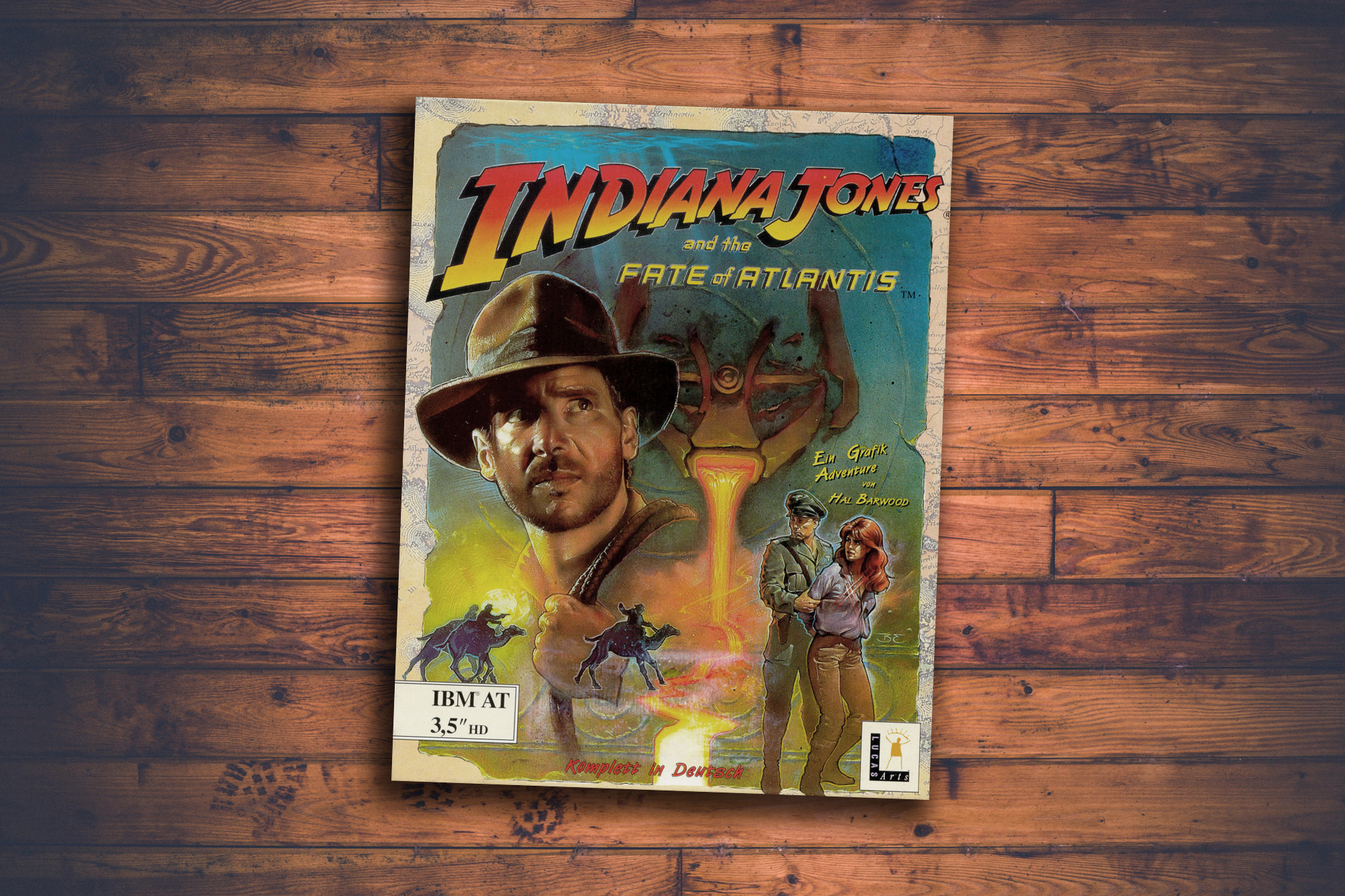

Being in some way a successor to the movies however also meant that the game had to fulfil certain expectations. Judging from the box of the game, the player was about to embark in a typical Indiana Jones movie adventure. LucasArts surely delivered. Punching Nazis, solving ancient mysteries as well as a love-hate relationship with his beautiful female companion are truly themes of the franchise. So is unfortunately also Orientalism.

What is Orientalism?

The term Orientalism was coined by Edward Said, a professor of English Literature at Columbia University, in the late 1980ies. For Said, Orientalism was and is the way the West (Europe and America) is interacting with the Middle or Near East, the so-called Orient. To use a more neutral term, I will speak of West Asia henceforth. Starting with the French occupation of Egypt by Napoleon of 1798 and enduring until today with the modern politics of the United States and also other first world countries, Orientalism is a western way of “handling” West Asia by occupation, suppression and differentiation.

Today, we talk about Orientalism when we depict cultures of Syria, Turkey or Egypt in a certain stereotypical way. This way usually demeans these cultures in comparison to the West. A whole art style is dedicated to depicting West Asia by white artists and also travellers. We as Westerners got so used to these depictions, that we rarely recognize these stereotypes anymore. We do not see them also while watching Orientalism in Indiana Jones movies and games. Sin, lust and decadence of west Asian cultures are typical themes of these pictures. Today, the depiction of lazy or uneducated Arabs is still present in movies or videogames. Depicting cultures of West Asia as terrorists is also a common theme of today’s Orientalism.

Orientalism in its core sense is not restricted to West Asia alone. We also speak of Orientalism, if we do the same to cultures of South America or Africa. As long as we as Westerners depict other cultures as inferior to us, we are practising Orientalism and that is saddening.

Orientalism in the Fate of Atlantis

But let’s talk about the Orientalism in Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. Since the movies, we already know that Indiana Jones is a artefact robbing or destroying nemesis. There is also a lot of Orientalisms there, but I want to focus on the videogame here. There are two distinct situations that need explaining.

Tikal

Pretty early in the game, we travel to Tikal to meet with Dr. Charles Sternhart, an expert on Platos fictional and also long lost third dialogue about Atlantis. Dr. Sternhart is currently working in a Maya pyramid to which he seems to have full authority over. He only grants us access after answering a Plato-related question to him. Inside, he tells us also, that he thinks that this pyramid was not built by the Mayans. In his opinion it was built by Atlantians. Of these former rulers, he suspects one king to be buried here, although he did not find the grave yet. After some questionable methods of finding the grave, Indiana Jones finally opens up the chamber to find an ancient stone disk. Dr. Sternhart euphorically steals the stone disk to exit the pyramid through a secret door.

Orientalism and Indiana Jones

So what is the problem here? First and foremost the person of Dr. Sternhart. Charles Sternhart is an English archaeologist and also antiquities dealer. Clothed in typical colonial tropical outfit he personifies the English aristocrat of the British Empire. While he obviously sells artefacts to visitors he also seems to have every right upon the Mayan pyramid itself. He also mentions his theory of the Atlantians building that pyramid. Denying the Mayans building the pyramid and therefore being cultural heritage to their ancestors in Guatemala is an act of appropriation. By attributing the creation of the pyramid to a long lost (and fictional) civilisation, Dr. Sternhart gives himself the right to rob this site as he wishes. These theories are nothing new, people constantly attribute the building of pyramids to paranormal activity or aliens.

Orientalism starts where Westerners demean non-white cultures. By taking the achievement of building these monuments from the Mayans (and therefore the people of South America) and attributing it to a fictional culture that conveniently mirrors modern European cultures, the game not only supresses non-white cultures, but also legitimizes the appropriation of ancient artefacts. Orientalism and Indiana Jones are going together here.

Algiers

A bit later in the game we travel to Algiers to meet with a local merchant named Omar Al-Jabbar. From him, we get some information to find more of the stone disks that we already encountered in Tikal. Al-Jabbar is a stereotypical West Asian, an obese merchant, trading in antiquities and also information. The game depicts the city of Algiers with a knife thrower, a beggar and other merchants, resembling scenes from the first Indiana Jones movie. The people depicted here are incapable of solving their own problems and Indy is there to help. Constantly, they thank him, also calling him “Effendi”, as if he is their rescuer.

So what we see here is a so-called White Saviour Trope, where the white protagonist solves the problems of non-white people. This clearly imperial behaviour is based upon the believe that non-white people are not as evolved as white people are. This goes way back to the 19th century, where Darwinism was the newest trend and especially European but also North-American people saw themselves at the forefront of evolution and everyone else… well not. Depicting non-white cultures this way is Orientalism in its purest form, by clearly distinguishing them from us.

“No bother Effendi” – Orientalism and Indiana Jones

Finally, we reach Atlantis at the end of the game, where we need to solve a couple of riddles, including the repair of Atlantian robots, driving an Atlantean drilling machine and also finding an Atlantian machine that turns humans into gods. We clearly enter the realm of pseudo-archaeology and even paranormal activity here. As Atlantis is pure fiction, there is no direct connection between Orientalism and Indiana Jones here, but the end of the game stands for the problem of the game as a whole. It is not Atlantis that is the problem, but rather – as I already described for Tikal – the notion, that human achievements are really made by a fictive and also supernatural civilisation. This in some way legitimizes Indys behaviour of stealing and trading artefacts, because these do not belong to anyone really.

In the end, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is in line with the whole Indiana Jones franchise, treating Cultural Heritage as if it belongs to white people only. In some way, the game depicts archaeology as it really was at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. Archaeology was build on Imperialism and also Indiana Jones depicts it that way. Nevertheless do videogames (or movies for that matter) depict this Orientalism still today, even if they depict it in the 1930ies. Of course there are also other examples too. This way, gamers get exposed to that way of thinking and learn, that it is the way West Asia seems to work, which is far from the truth. So, I do bother Effendi, I do.